New evidence shows that people have lived inland in Western Australia for more than 50,000 years. That’s 10,000 years earlier than previously known for Australian deserts.

The finding comes from archaeological work performed at the request of the traditional custodians of the land, and published today in PLOS One.

The research took place at the desert rock shelter site of Karnatukul (previously known as Serpent’s Glen), around 800 kilometres southeast of Exmouth - more than 1,000km from where the coastline would have been at this earlier time.

Read more: When did Aboriginal people first arrive in Australia?

It shows that people occupied the sandy deserts of interior Australia very soon after settling the north of the continent more than 50,000 years ago.

The paper reports some of the earliest evidence of people living in deserts, not just in Australia, but anywhere in the world.

Excavations old and new

Karnatukul was first investigated by archaeologists in the 1990s. At that time it became known as the oldest Western Desert site, occupied at least 25,000 years ago.

Our current excavation was undertaken to better understand more recent occupation evidence. We were trying to understand pigment art that was produced at the site during the past 1,000 years.

As well as finding rich evidence for a range of activities in recent times, our investigation doubled the earliest known occupation dates for this site.

Charcoal associated with artefacts was recovered in two squares dug beneath the site’s main rock art panel. Both squares returned similar archaeological sequences - both with their earliest radiocarbon determinations hovering close to the radiocarbon technical dating barrier which is 50,000 years.

Early tool shows technological innovation

More than 25,000 stone artefacts were recovered from the current excavations of Karnatukul, along with pigments, charcoal from many hearths, and a small amount of animal remains - a glimpse into the diet of the site’s occupants. Most of these remains date to the last millennium.

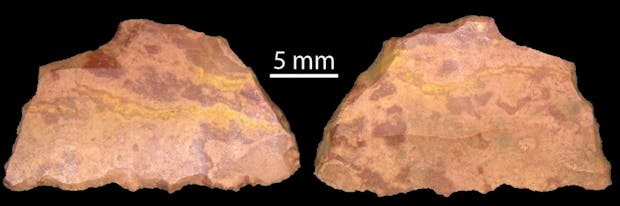

But one of our significant finds shows these early desert peoples were technological innovators. An early backed microlith – a pointed tool with one sharp edge blunted with small flakes, called backing - was found in deposits dated to around 43,000 years ago. Such tools are used as either a spear barb or for processing wood and other organic materials.

This tool is at least 15,000 years older than other known Australian examples. Other specimens have been recovered from the arid zone in South Australia, dated to around 24,000 years ago.

Microscopic analysis of residues and working edges on this tool reveal it was fastened by resin to a composite implement (such as to a wooden handle) and it broke in that haft, presumably while being used.

These technological adaptations - backing and hafting - are much earlier than had been previously demonstrated in Australia.

These types of tools were produced in enormous quantities across most of southern and eastern Australia, in the recent past. Indeed, Karnatukul has a large collection (more than 50) of this tool type dating to the last millennium, when the site was used as a home base.

Adapting to a changed environment

It has been argued previously that these specialised tools became more common as a people responded to increased climatic volatility and less secure food resources, with an intensified El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) regime after 4,000 years ago.

These current findings support the notion that the First Australians adapted with ingenuity and flexibility as they quickly dispersed into every bioregion across the country.

For instance, evidence for the earliest ground-edged axe use in the world comes from the Kimberley.

The very early presence of people in the interior deserts of Australia, as well as their very early use of a backed microlith, changes how we understand the adaptive and technological sophistication of early Aboriginal peoples.

The arid zone has often been characterised as an extreme environment occupied only by transient dwellers. Several European explorers perished in their early attempts to explore and traverse Australia’s arid core.

Cultural connections to the land

The site is in the remote Carnarvon Ranges of the Western Desert. Known as Katjarra, these ranges are at the heart of Mungarlu Ngurrarankatja Rirraunkaja ngurra (country), in the Birriliburu Indigenous Protected Area (IPA). Located in the Little Sandy Desert, this remote IPA covers an area the size of Tasmania.

Katjarra is of very high cultural significance to its traditional custodians.

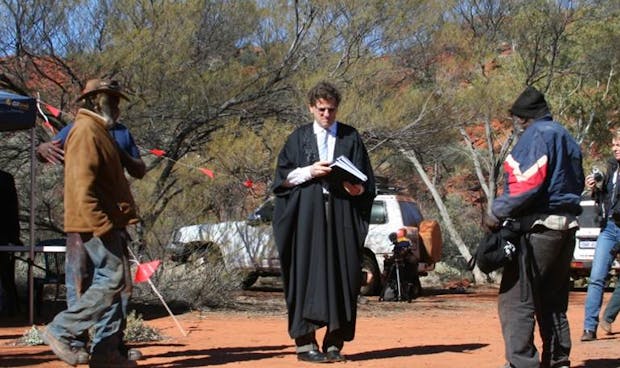

This archaeological evidence for the earliest desert peoples in Australia was found within 100m of the place where the Federal Court convened in 2008 for the Birriliburu Native Title Determination.

But the site is also only about 40km from the historic Canning Stock Route (CSR), a 1,800km track forged through the sandy deserts by Alfred Canning in 1906-07, reliant on numerous Aboriginal water sources, identified and named for for him by local Aboriginal people.

Because of the CSR, the Carnarvon Ranges have been at risk of unwitting damage from tourists – as modern desert crusaders travel this challenging and remote 4WD track. For example, many of the site’s surface grindstones - used for millennia to process seeds - have been collected and used by tourists to make camp fires, and there is graffiti where some travellers felt it necessary to add their names to rock features.

The Carnarvon Ranges are currently closed to unaccompanied tourists. The custodians have a responsibility for the safety of visitors on their country, intrinsically tied to the duty of ensuring that people do not unknowingly visit restricted and culturally powerful sites.

So the challenge now is how to protect this site of ancient occupation.

Read more: Time to honour a historical legend: 50 years since the discovery of Mungo Lady

The Birriliburu IPA has a management plan for this vast cultural and natural desert estate. Traditional Owners and younger rangers work in this IPA to care for country and to continue their long-held connections to this place.

Guided tours of this highly significant area with traditional custodians would ensure the protection of heritage places and visitors, as well as providing for sustainable tourism opportunities.

That way, people would still be able to experience a place that revolutionises our understanding of the first Australians who made one of the world’s driest continents their home. ![]()

Jo McDonald, Director, Centre for Rock Art Research + Management, University of Western Australia and Peter Veth, Kimberley Chair in Rock Art and Professor of Australian Archaeology, Centre for Rock Art Research and Management, University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.