Mikiel Anton Vassalli has now turned into an icon… no, the icon of Malteseness. Rejected, misunderstood, demeaned, criminalised for many years, only relatively recently has the nation started to acknowledge, slowly and perhaps reluctantly, the unpayable debt of gratitude it owes this enlightened trailblazer.

Vassalli was not the very first Maltese man of literature to succumb to the lure of the indigenous language. Others had preceded him, like the Magri brothers, Domenico and Carlo, who, over a century before Vassalli, had already placed on record their enchantment with the arcana of their native tongue.

A postage stamp that was issued by Maltapost to commemorate Vassalli.

A postage stamp that was issued by Maltapost to commemorate Vassalli.The Magri brothers, though probably the only Maltese bestselling authors throughout Europe in the seicento, have suffered a fate worse than Vassalli. Their originality, their erudition, their pioneering the value of the Maltese language still languish virtually un-acknowledged.

Frontispiece of the Maltese grammar published by Vassalli in Rome.

Frontispiece of the Maltese grammar published by Vassalli in Rome.Though not the first Maltese to place his native tongue on the pedestal it had been deprived of for centuries, Vassalli certainly remains the man with the sense of mission, the understanding, the determination and the fortitude to bring about the big climate change: the recognition of Maltese as a primary component of our nationhood.

The almost complete abyss of forgetfulness that engulfed Vassalli’s memory after his death till its slow renaissance 100 years later has helped obliterate plenty of documentary evidence that would have shone a more powerful light on his persona.

Portrait of Grand Master Emanuel de Rohan to whom Vassalli addressed his request to be allowed to open a school for teaching Maltese.

Portrait of Grand Master Emanuel de Rohan to whom Vassalli addressed his request to be allowed to open a school for teaching Maltese.Today, I will focus on a petition addressed by Vassalli in 1795 to Grand Master Emmanuel de Rohan to be allowed to open a school dedicated exclusively to the teaching of reading and writing in Maltese. This ought to be seen as a revolutionary project, never attempted before.

The population of Malta had, for centuries, assumed the spoken language to be Maltese but their written language to be Italian; not by any official diktat but by natural choice brought about by a blend of historical, social and traditional influences.

Sicilian and, later gradually, Italian for centuries, had been the language of the administration, of the courts, of the Church, of education and learning, of the professions, of commerce. Even the Order of St John, predominantly French, adopted Italian as its language of administration, when it settled in Malta.

The concept of a distinctive language as an indispensable part of nationhood was Vassalli’s most fundamental contribution to the fostering of a ‘patriotic’ identity. This petition shows Vassalli the monomaniac – he first wrote a grammar of the Maltese language, then a dictionary and completed the cycle by the more proactive measure of hands-on founding a school dedicated entirely to the teaching of Maltese. Only 31 years old, he had already achieved all that.

An idealised modern portrait of Mikiel Anton Vassalli.

An idealised modern portrait of Mikiel Anton Vassalli.Is the petition preserved in the Archives of the Order, the autograph writing by Vassalli or did he make use of a scribe? He certainly had the competence to write it himself as he was highly literate.

I have tried to compare the handwriting with other known writings by him and have not reached a definite conclusion. In some respects, the handwriting seems to be his, in others it varies. The jury is still out. It was not uncommon for less literate persons to employ the services of professional letter-writers.

Vassalli’s signature

Vassalli’s signatureThe unctuous, fawning wording of the petition hardly gives away the revolutionary simmering in Vassalli, nor do the superlatives used to butter up the grand master give any forewarning that its author would soon − in May 1797 − inspire a foolhardy and unsuccessful revolt against the rule of the Order. That style only reflected the stereotyped and formulaic way a private individual would seek grace from the majesty of the sovereign.

These petitions, though formally addressed to the grand master, actually fell under the jurisdiction of his bureaucratic structures. The grand master, in fact, wore two very separate and distinct crowns – he was head of the Order of St John and, concurrently, but only incidentally, also prince of Malta.

While the Maltese had virtually no say at all in the governance of the Order, grand masters delegated the administration of the island to their ‘civil service’ which was composed almost exclusively of Maltese officials and bureaucrats.

This massive participation of the natives of Malta in their own government is a factor that Maltese historiography frequently overlooks and devalues. The judiciary, the government departments, the prosecution services, the maritime and customs authorities, the police, the charitable institutions were predominantly manned and run by Maltese.

“That there are crooks everywhere you look has a long tradition”

On top of the bureaucratic pyramid sat the powerful Uditori of the Segnatura, almost all Maltese with a legal background. They exercised mixed judicial and ministerial functions.

They granted permits and licences, approved or refused petitions and requests for amnesties and even had the prerogative to modify court judgments. They exercised the power of life and death over ordinary people.

A few acquired a reputation for fairness and integrity. The majority were deemed the epitome of greed and seen as the most corrupt ministers of state. That there are crooks everywhere you look has a long tradition. Many ended inordinately and unexplainably wealthy and built the most sumptuous palaces on unimpressive salaries. As Vassalli would say in Maltese, “għax kellhom il-mara tibża għas-sold”.

Permission for Vassalli to open the school signed by auditor Raffaele Crispino Xerri.

Permission for Vassalli to open the school signed by auditor Raffaele Crispino Xerri.Mikiel Anton Vassalli’s petition ended in front of the Maltese Uditore, Raffaele Xerri, whose name was never knowingly tainted by corruption, possibly because he was already wealthy anyway, and who approved Vassalli’s request on April 11, 1795, fiat ser. ser. (servatis servandis) – granted, reserving all that is to be reserved.

Dr (later Sir) Raffaele Crispino Xerri, the son of Giuseppe, was born in 1746 and started his law practice aged 20. Only 30 years old, he became judge of the Civil Court and, two years later, was appointed Uditore of the Segnatura, which position he retained until the abolition of the Segnatura by Sir Thomas Maitland in 1814, when he was named member of the Supreme Council of Justice until he retired in 1824.

He was deeply versed in civil and canon law. When the governor instituted the Order of St Michael and St George in 1818, Xerri received the Grand Cross (GCMG). He died, 90 years old, on February 24, 1836.

Frontispiece of Vassalli’s Lexicon, a dictionary of Maltese into Latin and Italian.

Frontispiece of Vassalli’s Lexicon, a dictionary of Maltese into Latin and Italian.Not unexpectedly, Vassalli premised his petition with a short bio note hinting to his educational career path both in Malta and in Rome, without going into much detail. He claims to have been well-educated in belle lettere, philosophy and theology. This obviously refers to the period in which he had undertaken his studies for the priesthood in Malta, until he had a change of heart and abandoned his early vocation. He then mentions his studies in law, history and oriental languages, very likely undertaken in Rome. These, he implies, qualified him to run a public school.

The Roman seat of learning La Sapienza, where Vassalli studied oriental languages.

The Roman seat of learning La Sapienza, where Vassalli studied oriental languages.The information volunteered in Vassalli’s petition of April 1795 about his great Maltese – Latin – Italian dictionary “about to see the light” in Rome may have been slightly optimistic.

Vassalli had entrusted its printing to Antonio Fulgoni, a prominent Roman typographic establishment, with a special interest in the publication of texts in exotic languages. The dictionary did not actually see the light before the passage of at least another year, in 1796. Meanwhile, Vassalli remained in Rome, supervising the progress of the printing.

The Prospetto issued by Vassalli to promote a planned publication of his Maltese dictionary.

The Prospetto issued by Vassalli to promote a planned publication of his Maltese dictionary."His home in Żebbuġ was looted by the insurgents"

Many years later, Vassalli issued a long broadsheet, a prospetto (prospectus) inviting pre-subscriptions for the republication of his former dictionary but augmented by the inclusions of English and French versions. In this prospetto, he reveals that he had already finished these working manuscripts when he had to flee Rome in 1796, owing to the precarious political and military situation. He moved from Rome and withdrew to his native Żebbuġ, taking the unpublished manuscripts with him.

This building is reputed to be Vassalli’s home in Żebbuġ. Courtesy of Joseph P. Borg/Midsea books

This building is reputed to be Vassalli’s home in Żebbuġ. Courtesy of Joseph P. Borg/Midsea booksDuring the blockade of the French after the uprising, his home in Żebbuġ was looted by the insurgents; all his papers, including his precious manuscripts, were confiscated to turn into gunpowder cartridges, as paper had become unfindable in the countryside. To think that the genius of one highly literate patriot ended literally exploded through the zeal of other, less literate, patriots.

A rarely-seen portrait of General Vaubois, who commanded the French troops in the besieged harbour cities of Malta.

A rarely-seen portrait of General Vaubois, who commanded the French troops in the besieged harbour cities of Malta.This petition had not escaped the notice of some Vassalli scholars, among them Frans Ciappara, Joseph F. Grima, Frans Sammut and Karmenu Bonavia. I only wanted to add background to and some insights into this small fragment of the activities of a unique pioneer.

One observation on the contents of the petition confirms the ‘Malteseness’ of Vassalli. He was opening the school, he asserts, and proposing the teaching of Maltese in a scientific manner as, through it, the learning of other languages would prove easier; not because one is crippled by ignorance of one’s own language and not because learning is its own reward. No, a utilitarian carrot had to make learning Maltese attractive or, otherwise, the project would not get any traction in Malta.

Not a shred of evidence has so far surfaced as to whether Vassalli did in fact open his proposed school of Maltese as he had been authorised to do by the grand master. Or, if he opened it, what volume of business it attracted or for how long it remained active.

The Protestant cemetery outside Valletta where it is presumed Vassalli was buried after his death.

The Protestant cemetery outside Valletta where it is presumed Vassalli was buried after his death.Acknowledgements

The author thanks Maroma Camilleri at the National Library for her prompt assistance.

* * * * *

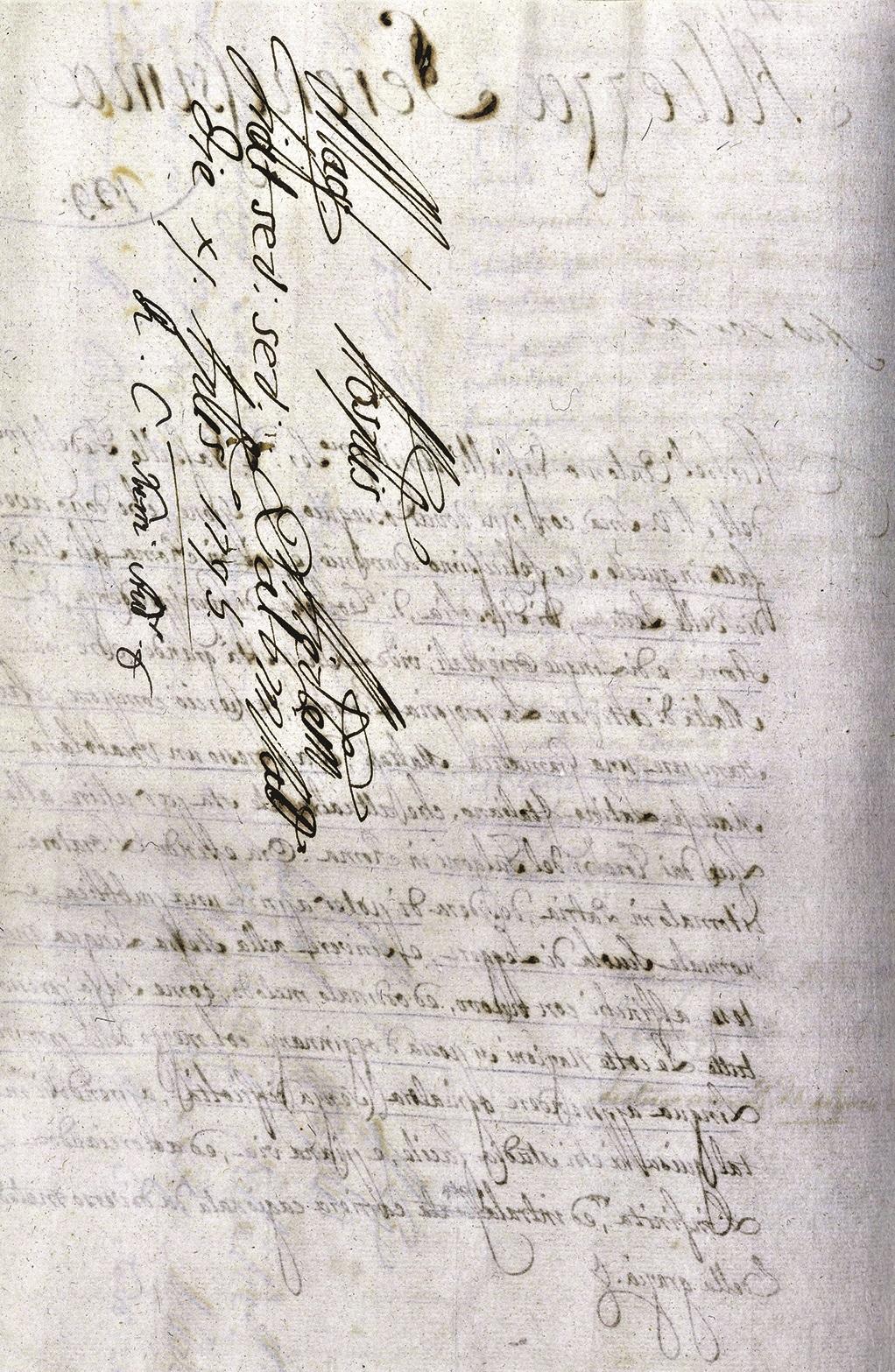

The 1795 petition by Vassalli to Grand Master Emanuel de Rohan to be licensed to open a school dedicated exclusively to the teaching of the Maltese language.

The 1795 petition by Vassalli to Grand Master Emanuel de Rohan to be licensed to open a school dedicated exclusively to the teaching of the Maltese language.Translation from Italian of Vassalli’s petition for a licence to open a school to teach Maltese

Your most Serene Highness,

Michel’Antonio Vassalli, most humble servant and most faithful vassal of your Serene Highness, with all due submissiveness states that, after having undertaken, in your most contented dominion, and later, in Rome, the studies of belles-lettres, of philosophy, of theology, of jurisprudence, of history and of oriental languages, became convinced of the great need Malta has to cultivate its own language. For this reason, he wrote and saw to the publication of a Maltese grammar, and after that, of a Maltese-Latin-Italian dictionary which is about to see the light from the Fulgoni printing press of Rome.

The petitioner, having now returned to his native land, desires to open a public and normal school [in Italian, scuola normale stands for regular, higher school] for the teaching of reading and writing in the said Maltese language so that, with a new and orderly method, as used in all well-learned nations, it will be possible, from now onwards, by means of one’s own language, to learn every other language without difficulties, opening up, in this way, for those who study it, an easy and strait road and thus shortening the infinite and [???? crossed out intralasciata changed to intralciata = complex] pathways resulting from other methods.

And, by grace,

Independent journalism costs money. Support Times of Malta for the price of a coffee.

Support Us