UK MPs have started to debate the final Brexit withdrawal agreement ahead of a “meaningful vote” which will still go ahead on Tuesday, despite a newspaper claim that it will be postponed.

There are various possible scenarios that might play out after that vote, some of which are outlined below.

1. MPs vote in favour of the deal

This is possibly the easiest outcome in terms of pushing forward with Brexit, but the hardest to obtain, given the sheer number of Conservative MPs who have said they will vote against the deal. A vote in favour would give the prime minister the power to tell the EU that the deal has been ratified by parliament.

But the government would still need to pass a hefty amount of legislation as the Brexit process continues. This would begin with the EU (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill – a piece of legislation which the House of Commons Library thinks could happen before Christmas.

In the event that this first option doesn’t happen (which seems increasingly likely), the future is all a bid muddled. This is partly because it depends if MPs vote in favour of any amendments to the motion on December 11. Here, the possible outcomes would be:

2. MPs vote against the deal but in favour of an amendment

The House of Commons speaker, John Bercow, can select up to six amendments to a proposed bill to also be debated and voted on by the house. In this case, the proposed amendments include one by Labour MP Hilary Benn to reject both the Brexit deal and a no-deal scenario in an attempt to enhance the power for MPs to find an alternative. Labour and the SNP have said they will support the amendment. Other amendments include extending the Article 50 deadline to give more time to decide how to proceed.

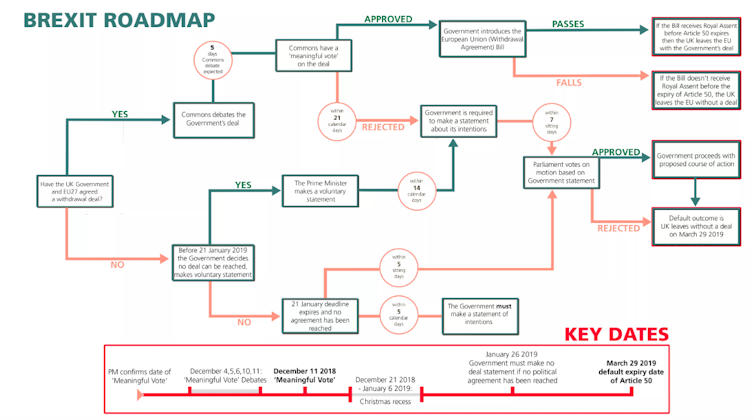

If MPs vote against the main motion on the deal, the government would give a statement to the House of Commons within 21 days setting out how it plans to proceed, as specified in the EU Withdrawal Act 2018. This would bring us to January 1, 2019. Parliament would be given a week to debate the contents of this statement, before a further round of ministerial statements reporting on progress by January 21.

This handy chart put together by parliament shows how this would all work.

If MPs vote in favour of any amendments to the motion on December 11, they will be trying to tie the prime minister’s hands and push for her to agree to parliament’s demands. This could be in the form of a second referendum, for which there is now considerable support on the opposition benches.

The cross-party amendment led by Conservative MP Dominic Grieve which passed in the House of Commons on the Tuesday before debating began means that parliament will be able to amend any later motions put forward by the government after the 21-day period too, pushing for alternative options. In an interview on the Today programme a few days later, the prime minister hinted that MPs may have more of a say on the detail of the backstop agreement on the Northern Ireland border.

Parliament could be asked to vote again on the deal. This was confirmed by chief House of Commons clerk David Natzler in evidence to the Brexit select committee just over a month ago. At the time, he said it was a “hypothetical question” but confirmed that there were ways in which it could happen as the procedures of the House would not want to obstruct progress.

3. MPs trigger a vote of no confidence in the government

Keir Starmer, Labour’s Brexit spokesman, has said the party would “inevitably” call a vote of no confidence if the prime minister loses the vote on December 11. MPs would have to vote on a specifically worded motion, in accordance with the Fixed Term Parliaments Act, saying “That this house has no confidence in HM government”.

If MPs voted in favour of the motion, it would trigger a two-week period in which a new government could be formed. Only if this failed would a general election be triggered. MPs may not be eager for a general election, particularly with the Brexit clock ticking. If the prime minister survived a no-confidence vote, there would be increasing pressure on Conservative backbenchers to support her on the Brexit deal.

There is also the outside option that the prime minister herself could ask the House of Commons for an early general election, but this would require a super majority of two thirds of MPs voting in favour.

What makes this even more complicated is that the formal parliamentary route to Brexit is sitting alongside a party political one. So alongside the various legal options, we also see the possibility that May could face a leadership challenge from her own party.

4. Theresa May resigns as party leader

If she loses the vote on the final deal, May might resign, triggering a leadership election within the Conservative Party. At the moment, it seems anything is possible, but given her emphatic statement last month that she believed with her head and her heart that “this is a decision which is in the best interests of our entire United Kingdom” it seems unlikely.

And while the party took just 17 days to decide on May as the next leader when David Cameron resigned, it generally takes a lot longer. A full contest would likely drag on through January. And with the latest survey of party members showing a clear lead for Boris Johnson as the favourite to take over as party leader, MPs may be forgiven for thinking that they are safer to stay with May for now.![]()

Louise Thompson, Lecturer in British Politics, University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.