This collection of portraits by Johanna Barthet reminds one of Oscar Wilde’s words: “I like men who have a future and women who have a past.” The past is fertile ground for storytelling, for contemplating on documented experiences, for extracting the morale in a haphazard sequence of unfolding events. Protagonists are sometimes lauded and glorified, others are derided and punished, while others are largely forgotten.

Johanna Barthet

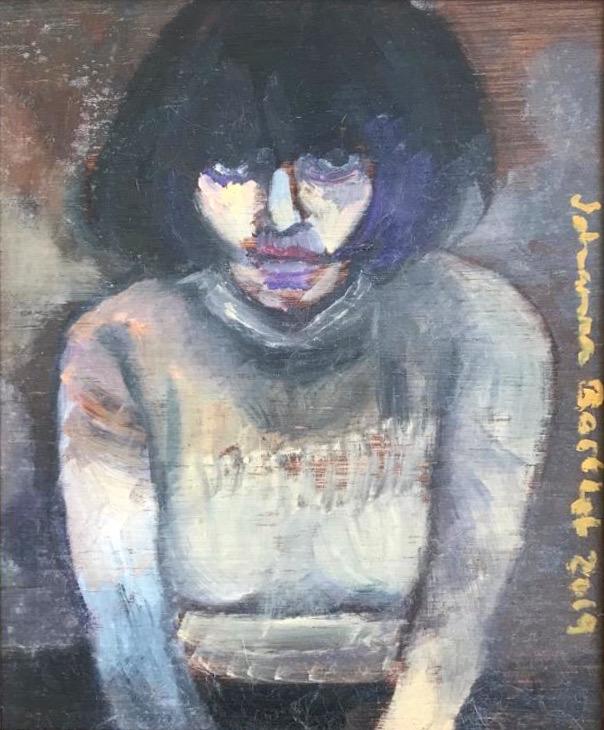

Johanna BarthetStories Untold, her first solo exhibition back in March 2019, introduced a newcomer to the Maltese art scene via a genre that, in today’s world, has become of secondary importance as a vehicle for artistic expression. Digital photography has democratised the process of capturing images, even replacing its analogue counterpart that had revolutionised the genre of portraiture in the first half of the 19th century, and that had sent sensational portraitists like Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres spiralling into an identity crisis.

Mobile phone cameras have flooded social media with selfies; the instant documentation of the present and the mundane has achieved overwhelming precedence in our lives. It seems urgent to let the world know that we actually have a life, ironically declaring to all and sundry that by doing so, we actually don’t.

One can regard Barthet’s portraits as an act of freedom for the stories of these girls and women, by relieving them from their humdrum imprisonment in magazine pages and Instagram accounts. She invigorates their tales through colour and narrative, reinterpreting their past as the social media images are frozen in pixelated time, their relative relevance dependent on the number of likes, the shares and the comments that they attract.

‘The Coffee Shop’

‘The Coffee Shop’The photos of the women in magazines these days owe their origins most probably to digital cameras, the numerous pixels once again reconstructing some notion of reality. The Maltese artist eases out their personalities from their aseptic virtuality, attenuates their fakeness by recontextualising them on canvas while deftly reincarnating them through her brushwork. Barthet thus breathes a soul unto them.

Russian author Leo Tolstoy, in his novel Anna Karenina, claims that “rummaging in our souls, we often dig up something that ought to have lain there unnoticed”. One feels that these words somehow explain the spirit behind this collection of portraits of unidentified women. A part of the Maltese artist’s own spirit, a soul-searching, has been weaved into the fabric of these depictions – Barthet’s identity as a woman, her own biographical references, her artistic baggage – merges with the congealed spirit of the women; the springboards for these virtual/real hybrids, these simulacra, these re-imagined protagonists of past stories.

‘Girl on a Stool’

‘Girl on a Stool’The particular dimensions of the room, which essentially define its ascribed moniker, refers also to the artist’s state of mind

The immediacy and the urgency to deliver news, even if it is of the most personal nature and not of special general interest, contributes to the denigrating ‘pass’ appellative that is so widely banded about by modern culture. Yesterday’s news is old news is an aphorism that can be rephrased as last hour’s news is ancient news.

French sociologist Jean Baudrillard had insightfully stated that society has lost all orientation with the real world as it has become reliant on models and maps that preceded them: “The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory ‒ precession of simulacra ‒ that engenders the territory. It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real.” And this is the sad sign of the times of contemporary living.

‘Darkness’

‘Darkness’This crowd of women, convening in the intimate setting of Mqabba’s Il-Kamra ta’ Fuq, stare at us, rather reversing the role of the viewer. It is uncanny to have pairs of eyes sizing one up, through their discomforting and ubiquitous gazes of judgement, empathy or disinterest. The epitome of portraiture, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa’s stare is unsettling as her eyes seem to follow her admirers’ every movement.

The particular dimensions of the room, which essentially define its ascribed moniker, refers also to the artist’s state of mind; such a finite space being a safe space away from the noisy downstairs. Here she would be able, in solitude, to dwell on her thoughts and to reconfigure what needs to be figured out. She enjoys such a confinement in her studio at home too, which is a room upstairs too. Barthet metaphorically lays her safe space open for public scrutiny. This adds another layer to this exhibition, the artist’s third solo, aptly titled as The Little Room Upstairs.

Like-minded spirits

In Stories Untold, which can be regarded as the first chapter as a pictorial storyteller and purveyor of anecdotes, Barthet was inspired by like-minded spirits such as Paula Modersohn-Becker, Chantal Joffe and Chaim Soutine. The Maltese artist admires Joffe, a British artist who has a preference for portrayals of women who finds that the feminine offers more possibilities than the masculine. “I really love painting women. Their bodies, their clothes – it all interests me, whereas men really don’t that much, in a way,” Joffe once remarked.

‘Redhead in Red Scarf’

‘Redhead in Red Scarf’In an exception to this rule and reinforcing her preference for female models, the British artist portrayed her husband, Bacchus-like in his corpulency, naked, prostate and thighs spread, unabashedly exposing his genitals as the ultimate depiction of brash masculine virility. Barthet, just like her British counterpart, prefers portraying women and girls, for their flamboyance and their sensitivity, fully clothed and rather coy.

Although there are examples of portraits of men in the Maltese artist’s oeuvre, curator Melanie Erixon chose to investigate the Maltese artist’s predominant theme, femininity. Barthet eloquently describes these paintings as “putting love in a bottle”, through the capturing of the whaffs of ‘fragrance’ of feminine vulnerability and strength. These delicate portraits are like petals, furtively secreting their attar for us all to bottle and appreciate.

The Little Room Upstairs, hosted by Mqabba’s Il-Kamra ta’ Fuq and curated by Melanie Erixon for Art Sweven, runs up till May 16. Log on to the event’s Facebook page for opening hours.