Hors Concours is an exhibition celebrating female students at the University of Malta since their enrolments began, with 100 years of stories, photographs and facts. Laura Swale invites its curator Professor Raphael Vella to talk about the history of women at the university and the power of art

Professor Vella, when first approached to curate this all-female exhibition, you initially felt you might be ‘the wrong gender’ for the job. Why do you think you were asked, and now that the exhibition has opened, how do you feel about being involved?

I guess I was approached on the basis of my curatorial portfolio and also another exhibition called Building Futures I curated on campus in 2016. Curating a gender-related exhibition is never easy. I wanted to avoid portraying something very complex in a generic way, so I involved several other people in the organisation of the exhibition, particularly women.

Can you explain the show’s title Hors Concours?

The title is lifted from the minutes of a university council sitting in 1923 which discuss briefly a number of applications for the post of Professor of English Literature. The minutes explain that 16 applications were received for this post, four of which were from ‘ladies’. They go on to say that ‘for obvious reasons’ these women were considered to be ‘hors concours’.

Raphael Vella

Raphael VellaNow, this term can be understood as a direct exclusion of the women (literally ‘out of the competition’) but it is also used sometimes to refer to someone who is without equal. I quite like this ambiguity because it reflects the frictions that are inherent in the complex nature of gender equality. The second meaning of the term begs the questions: who would see women as being ‘without equal’, and hence a threat to one’s own success?

How has the proportional representation of women in the university’s student population evolved over time?

Since the early 1990s, the University of Malta has had more female students in many of its courses in most faculties. One must ask therefore where the ‘missing’ male students are going. Joining other institutions in Malta and abroad? Going immediately into employment? We definitely need more studies in the field to understand this and related issues, such as the low proportion of female academic staff at the University of Malta.

Curating a gender-related exhibition is never easy. I wanted to avoid portraying something very complex in a generic way

Is there any gender underrepresentation when it comes to specific subject areas within the expressive arts and if so, to what would you attribute this fact?

I would say that males are generally under-represented among arts students at the university. At least this is my experience. More students are female, but more lecturers and professors are male.

How would you describe the breadth of the work on display by these female artists and why might we enjoy a visit to the exhibition?

The exhibition is designed in a way that creates a dialogue between four artists’ perspectives and different ‘documentary’ artefacts on display, between fact and fiction. I started off with a bunch of old, black-and-white photos that were several decades old, showing some of the earliest female students, like Tessie Camilleri and Cettina Bajada. The monochrome homogeneity of those photos scared me because the last thing I wanted was to give the impression that we would present a singular ‘female’ experience of university life. So we issued an open call for more recent photographs and experiences, leading to a more co-creative approach to the curation of the exhibition.

This loosely ‘sociological’ method was also adopted by two of the artists, Kristina Borg and Charlie Cauchi, who interviewed many women for their work. Their artistic productions, respectively a performance piece and video art, were accompanied by a physical and audio installation by Margerita Pulè and paintings and drawings by Amber Fenech. We therefore have a heterogenous series of outlooks on the main themes of the exhibition, yet all the works remain stubbornly beyond ‘mere’ sociology and beyond academia.

The exhibition is deliberately imbued with a sense of internal contradiction: on the one hand, it throws cold statistics and dates at the viewer but on the other hand, its artworks ask questions, often in a nonverbal, ‘silent’ way. These moments of silence and doubt are the most poignant and possibly the strongest statement on women’s experience of higher education in the exhibition. Unlike statistics, they need to be experienced directly and cannot be explained.

Images from the open call for recent graduates.

Images from the open call for recent graduates.While it’s reassuring that women no longer face the same struggles they did back in 1923, we are now living in a world which acknowledges more than two genders. In this age of gender politics, non-binary genders and the concept of gender-fluidity, it could be argued that an entirely new group of people face a similar journey to that of the ‘hors concours’ women. You refer to ‘moments of silence’ as having power, when it comes to communicating without words, do you feel that art is uniquely placed to communicate complex issues such as gender and individuality?

Yes, it most definitely is, and many contemporary artists deal with a more fluid understanding of gender in their work. It’s relevant that art tends to say more than what it actually says, providing reformulations of gender with a fertile ground for presentation.

This ability to use colour, timbre, uncertainty, absence, and so on to convey a more affective domain gives art a special power to communicate a non-normative understanding of gender, but also ethics, justice, and so on. Those of us, including those who work in a university context, who prefer to remain perpetually in control of what they say and how their views are projected in public fora, are sometimes put off by this force that art has to extract something that lies just beyond the real.

What would you like people to know about the university’s work in the sphere of visual arts and your future plans?

I don’t think it is easy to summarise the university’s ‘work’ in this sphere because we actually have rather different philosophies of how to do and teach art within different faculties at the university. I tend to work in the spaces between artistic, educational and dialogical practices, and the projects, publications and degrees I work on reflect these interdisciplinary layers of practice. This year, we introduced a new Master’s degree in Social Practice Arts and Critical Education, which links visual art and performance to social engagement and pedagogy.

I am co-editing an international anthology of essays studying the imbrications of art, ethics and education. The book is being published by Brill/Sense and will be out in the next few weeks. I am also working on an international EU-funded project linking art education to sustainable development and another major project with several other European partners, in which we are leading the implementation of around 30 new artistic productions among marginalised groups in different countries. Ultimately, art provides us with the opportunity for exchange, breaking down or exposing barriers that separate the ‘acceptable’ from all that is hors concours.”

Hors Concours is open daily from Monday to Friday 8am-5pm and runs until November 29 at the University of Malta Valletta Campus.

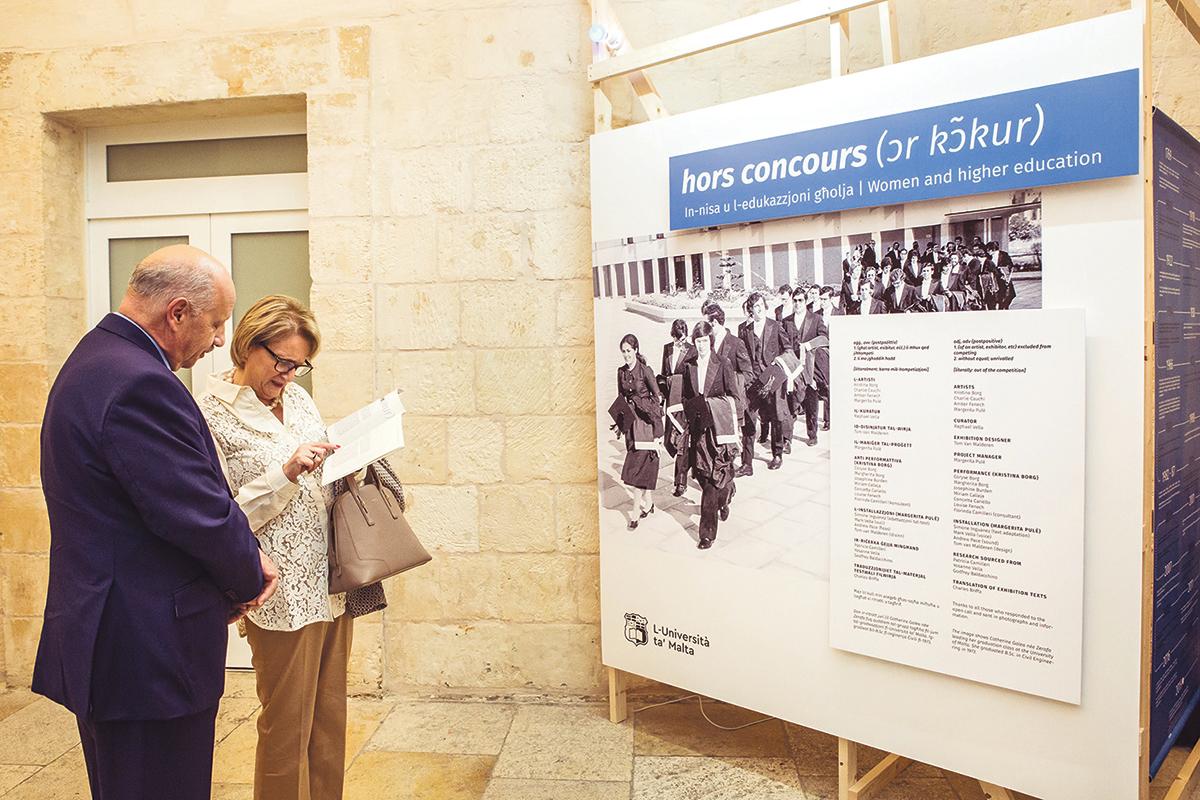

Rector Professor Alfred Vella in front of the exhibition’s welcome panel.

Rector Professor Alfred Vella in front of the exhibition’s welcome panel.