This is not the genre of books I am usually asked, or offer, to review, but gladly do I allow for an exception. George Cini seems to have made it one of his life’s missions to preserve in the naphthalene of memory the saga of those the majority of the self-righteous would rather see forgotten.

The fact that Maltese uses the classical Arabic q-ħ-b to denote whoring and whores, indicates conclusively that prostitution was well established in Maltese culture at least since the Arab conquest. But during the times of the Knights, Valletta had no red-light district to speak of. Commerce in women and pretty boys thrived – maybe more than today, if the accounts of visitors are to be believed.

Dolor Gouder, Rita McBee’s mum. Photo: Rita Mcbee

Dolor Gouder, Rita McBee’s mum. Photo: Rita McbeeA well-informed French author swears that two out of three women in Valletta earned their living horizontally. And when the inquisitor clamped down on gay sex, no less than a hundred boy-prostitutes fled from Malta in a panic. But the sex industry then worked mostly through capillary dispersion – sex commerce was everywhere and nowhere.

That changed radically with the arrival of the British. The greatest fleet in the world took over the Valletta harbours, and the laws of supply and demand reconfigured the current lazy scenario – a geographical segment of the city organised itself to service the thousands of sailors avid for entertainment, liquor, music and sex. The northern segment of Strada Stretta, later Strait Street, served as axis to a booming red-light district, with residential quarters and ancillaries crowding its sides.

Ġużi of the Cairo Bar in Strada Stretta. Ġużi was a cross-dresser who earned tokens like barmaids did. Photo: Ġużi Tal-Cairo

Ġużi of the Cairo Bar in Strada Stretta. Ġużi was a cross-dresser who earned tokens like barmaids did. Photo: Ġużi Tal-CairoI described elsewhere how my family lived in Old Bakery Street and, to reach the Lyceum in Merchants Street, I had perforce to cross Strait Street. My solicitous parents, fully paid-up members of the self-righteous brigade, made me swear never to stray into the depraved street, to cross only through an intersection where policemen usually stood guard and never even to look sideways when crossing. That, of course, made it more pruriently attractive.

This Strada Stretta book, together with the two which preceded it, is a tour de force of nostalgia harnessed to the narratives of the peripheries of life. Narratives of the cores of many lives, shorn of the boredom of social statistics and pointless moralising. Cini interviewed a considerable number of the survivors of the blessings of post-war Strada Stretta, and they air their daily struggles for assertion or survival.

The Colonial in Strada Stretta was a top-class restaurant known for its elegance. Photo: Victor Farrugia

The Colonial in Strada Stretta was a top-class restaurant known for its elegance. Photo: Victor FarrugiaThe author has transcribed, I believe with absolute faithfulness, their unsanitised stories, grammatical howlers and all. Very little individual epic transpires from these confessions, but heaped on top of each other, they end up as the epic of Strada Stretta. Every narrator, a senior citizen by now, records a lifetime of Strait Street experiences, many their forgettable successes and some their permanent failures. This is humanity in a minor key, but a very human, loving, caring humanity all the same – the streaks of veritable Christian compassion that run through several of these stories may bring tears to your eyes. They all witnessed the withering of the old riotous Gut when the British navy withdrew from Malta in 1979.

Cini has done an impeccable job in prizing this human dimension out of the many workers crowding the microcosm of the Gut ‒ the mentionable and less mentionable entertainment, their sense of belonging, the solidarity that bound many together, their instinct of survival. Many just played supporting roles to the main commodity – sex on offer or, in meagre times, on discount.

Ballerina in Strada Stretta cabaret show before WWII. Author’s collection

Ballerina in Strada Stretta cabaret show before WWII. Author’s collectionBakers, hairdressers, cooks, entertainers, cabbies, grocers, card sharps, taxi drivers, usurers, tattooists, all gravitated in or round ‘the Gut’. One I recall personally: the affable Pawlu t-Tork who pushed his bread cart through the streets of Valletta squealing pasta dura friska friska at the top of a well-manicured castrato voice and selling scrumptious bziezen which put the most redoubtable French baguettes to shame.

Many of the best light musicians in Malta had their baptism of fire in those haunts and went on to acquire national fame. I feel, perhaps wrongly, that Cini attempts to convey the impression of some glamour embracing the district. Try as I may, I see more squalor than glamour. Extremely human and empathy-friendly, but overall squalor just the same.

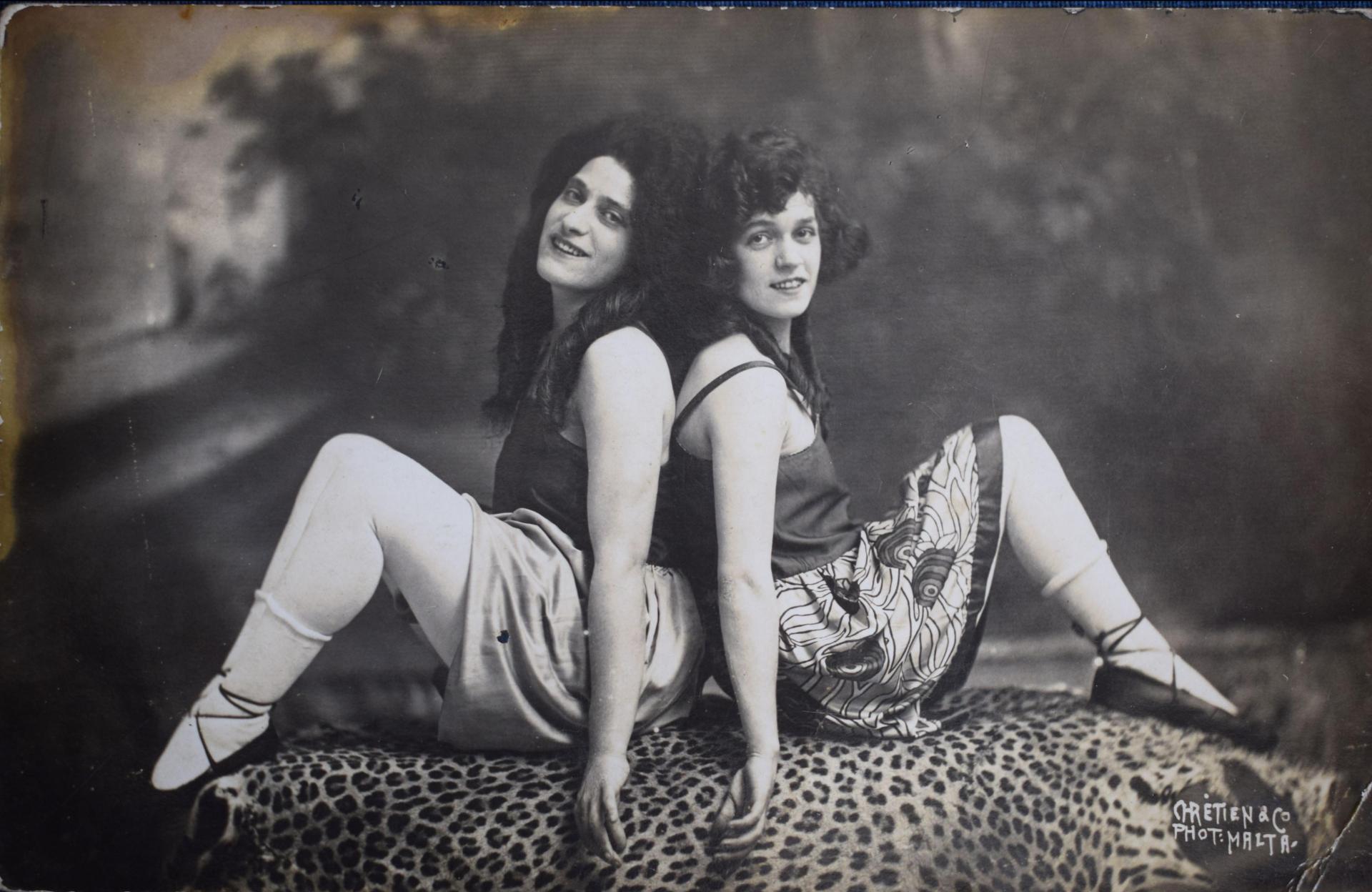

Transvestite entertainers in Strada Stretta before WWII. Author’s collection

Transvestite entertainers in Strada Stretta before WWII. Author’s collectionOver 20 surviving veterans of the Gut bare their innermost souls, with, I believe, little or no self-censorship. Among the glories figured transvestites, then called impersonators, apparently all-time favourites with British and American servicemen. And bouncers, then called chucker-outs.

Even the artist Paul Caruana, from Triq tal-Franċiżi, who illustrated these mini autobiographies with his lovely watercolours dripping charm and sometimes naughtiness too, adds his own personal nostalgia. As a kid, he confesses, he adored from a distance an unapproachable barmaid of incomparable beauty, whom he refers to as ‘the angel’. To this day, almost 50 years later, he believes she would still be unbeatable in any beauty contest. I hate to disappoint him, but today he would have to be prepared to overlook wobbly dentures, varicose veins and poorly dyed hair, a hearing aid perhaps.

Straight Street in the inter-war years. Author's collection.

Straight Street in the inter-war years. Author's collection.The whole district expressed its own special patois too. The raconteurs all seem to enjoy clipping words of foreign origin. No one lives in Strada Forni or passes through Strada Mercanti. It is always Sada. The gardens are Hastig and a guboks blares out music.

Plus that, the district seems to have held out as a last stronghold of old-fashioned nicknames, personal and family. You will find scores of them: il-Boqqu, il-Pasisu, il-Kuranta, il-Ganix, il-Brimbu, iz-Zingla, il-Futtru. And distinctive, if not distinguished, family names abound: tar-Razzi, tan-Napezz, tad-Dindu, taz-Zubba, tan-Nappa, tal-Gadoffa. The use of family nicknames has today dwindled, to the point of almost becoming non-U.

Frank Camilleri, il-Bibi, who was one of the top pianists of his time, during a training session with his son, Joe at the Kenner Bar, in South Street, Valletta. Frank and Joe started their careers in Strada Stretta. Photo: Joe Camilleri, Il-Bibi

Frank Camilleri, il-Bibi, who was one of the top pianists of his time, during a training session with his son, Joe at the Kenner Bar, in South Street, Valletta. Frank and Joe started their careers in Strada Stretta. Photo: Joe Camilleri, Il-BibiA well-organised name index makes this highly readable book also a work of reference. It has some unexplainable lacunae. Bice Vassallo, the talented pianist wife of the penniless Prime Minister Enrico Mizzi, taught music to some of the child prodigies who later shone in the Gut.

She is cited in the text but omitted in the index. And Dom Mintoff, who seems to have enjoyed a following of worshippers in Strada Stretta and its environs, though referred to more than once in the text, equally fails to make it to the index. I could mention a few others.

“In one of the tenement houses close to where we lived in St Joseph Street, a couple had a toddler who cried all day and night, making it impossible to enjoy a good night’s sleep.” Photo: Watercolour by Paul Caruana

“In one of the tenement houses close to where we lived in St Joseph Street, a couple had a toddler who cried all day and night, making it impossible to enjoy a good night’s sleep.” Photo: Watercolour by Paul CaruanaThroughout its 150 years of activity, the Gut enjoyed the most ambiguous of reputations, heaven of bliss to its adepts who still moan its passing away, veritable hell for its detractors – one seamless bordello masquerading as an entertainment hub. George Cini’s book tempers some of the romantic fiction haunting the place with his record of its irreversible decline and fall. Both sides end up being equally well served.