When the spire of Notre Dame cathedral collapsed in a fiery blaze on Monday April 15, it looked as if the priceless treasures inside would be lost forever. This includes sacred paintings, tapestries, sculpture, stained glass windows, as well as a cherished collection of holy relics.

So it was wonderful to see, the next morning, that the cathedral’s Gothic fabric – which is more than 850 years old – held strong. Its sweeping vaults are damaged but intact – testifying to the brilliant engineering of medieval masons and the bravery of the Parisian firefighters.

As the news of the destruction unfolded, we learned that Father Jean-Marc Fournier orchestrated the rescue of many relics in the cathedral treasury with the firefighters’ help. With minutes to spare, they formed a human chain and managed to save some of the most ancient and holy treasures in all of Christendom – including the relic of the Crown of Thorns.

Preserved in a gilded, crystalline reliquary and exposed to the faithful every year for a special service on Good Friday, the crown relic looks like a wreath comprised of brittle but elegantly woven marine rushes. This delicate relic has a long and complicated history and, for the past eight centuries, has been protected by glittering Gothic spaces and worshipped in Paris as tangible, physical symbol of Christ’s kingship. In the wake of the fire at Notre Dame and on the eve of Good Friday, it is important to reflect on the significance of this sacred object and its remarkable survival.

‘Ecce homo’

The Crown of Thorns is named in three of the gospels as one of many tortuous instruments used while Christ is being mocked during his trial and punishment (Matthew 27:27–30, Mark 15:16–19, and John 19:1–3). In John’s gospel, the Passion narrative is extended: Christ is brought before the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, to face the crowd while still wearing the Crown of Thorns.

This passage forms the basis of the popular devotional image called the Ecce Homo, in which Christ is imagined as the rejected Messiah, scourged and crowned in thorns. The gospels do note state what became of the Crown after the Mockery.

Interestingly Christ does not wear the Crown of Thorns in early depictions of the Crucifixion. Christ is shown dying on the cross without the crown (with only a handful of exceptions) throughout the first millennium of Christian art. And the existence of a relic cult is unknown until the fifth century. In 409 AD, Saint Paulinus) instructed the faithful to venerate Holy Thorns relics in the basilica of Mount Zion in Jerusalem, alongside the Flagellation column and the Holy Lance. In 591 AD, Gregory of Tours offered the earliest known description of the crown relic:

They say that the Crown of Thorns appears as if it is alive. Everyday its leaves seem to wither and every day, they become green again because of divine power.

On the road

Only a few accounts of the crown relic at Mount Zion exist after the siege of Jerusalem in 636 AD, due to difficulties in access for pilgrims. A True Cross reliquary, known as the Limburg Staurotheke, is our earliest material witness to the relic’s new location in Constantinople. Fashioned in about 950 AD, its inscription states that it holds items from the Byzantine emperor’s treasury, including a fragment of the Crown of Thorns. But it remains unclear when or how the crown came to Constantinople, where it was enshrined near in the Bucoleon palace amidst a marvellous assortment of Passion relics.

Writing during a political coup in 1200, Nicolas Mesarites, the palace guardian, praised the survival of the “incorruptible” Crown of Thorns, which was “fresh, green, and un-withered”. After the Fourth Crusade, Baldwin of Flanders became the first Latin emperor of Constantinople and took control of the palaces and their treasuries.

In 1228, when Baldwin II took the throne at the age of just 11, crisis seized the Latin Empire. To secure money, he pledged relics as debt collateral. Around 1237, the Crown of Thorns relic was used to secure a loan from a wealthy Venetian merchant named Niccolo Quirino. Baldwin ventured to Europe on a fundraising mission and approached his “cousin” King Louis IX of France (1214–1270) for more help and the French king agreed to pay off the imperial debt.

A divine gift

In so doing, Louis IX would become the new protector of the relic. To be clear, this exchange was not a sale, as this would have violated ecumenical rules. Instead, the transfer of the crown from Constantinople to Paris would be framed as a diplomatic transaction and celebrated as a divine gift.

Gauthier Cornut, a 13th-century archbishop of Sens, wrote a detailed account of the transfer of the crown to Paris in a text known as the Historia Susceptionis Coronae Spinea. He also orchestrated a number of ceremonies to commemorate the arrival of the relic. Removing his crown and wearing only a humble tunic (another holy relic saved during the fire at Notre-Dame), Louis walked barefoot carrying the relic into Paris in a spectacular procession on August 19, 1239.

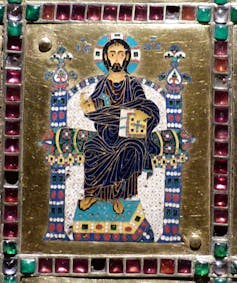

The parade ended with a sermon inside Notre Dame cathedral before the relic was locked away in the royal palace. Just nine years later, on April 26, 1248, the Sainte-Chapelle was consecrated in honour of the Passion of Christ. This shimmering, two-storied Gothic edifice enveloped the Crown of Thorns in a dazzling curtain of Gothic glass and colour, providing an extraordinary stage for the celebration of Christ’s presence right in the heart of Paris.

It is here that we first find numerous images of Christ crucified wearing the Crown of Thorns, a thoughtful reinvention of Christian iconography that places the object at the centre of salvation history. In 1297, 27 years after the death of Louis IX, he was canonised; the piety of Saint Louis throughout his life was extraordinary, but his acquisition and procession of the relic was arguably one of the earliest and most public demonstrations of his sainthood.

A new home

The Crown of Thorns remained in this royal chapel until the French Revolution. In 1790, some of the relics were safely delivered to the abbey of Saint-Denis and, in 1806, Archbishop Jean-Baptiste de Belloy of Paris oversaw the transfer of the relic to the treasury of Notre Dame, where it could be worshipped by all of the people of Paris as a shared, civic treasure.

It has remained in the cathedral, enduring the violence of the Commune and two World Wars, until calamity struck on April 15. It will be housed at the Hotel de Ville during the rebuilding of Notre Dame.

Read more: Japan's PM has frog in throat as ecological crisis looms

Throughout innumerable wars, disasters, other threats from the vicissitudes of time, this small, sacred object – a little cluster of ancient branches that signify Christian salvation – still remains. Loved by thousands, the Crown of Thorns relic continues to serve its purpose – to inspire hope, to remind us that what is lost can one day flourish again and that the things we love, no matter how small, have great power.![]()

Dr Emily Guerry, Senior Lecturer in Medieval History, University of Kent

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.