In her State of the Union address on 13 September, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen announced a new anti-subsidy investigation into electric vehicles (EVs) from China, claiming that the market is being flooded by cheap imports at prices that are kept artificially low by “huge state subsidies”. The move was widely reported to be a reaction to pressure from France; other member states, notably Germany, were opposed.

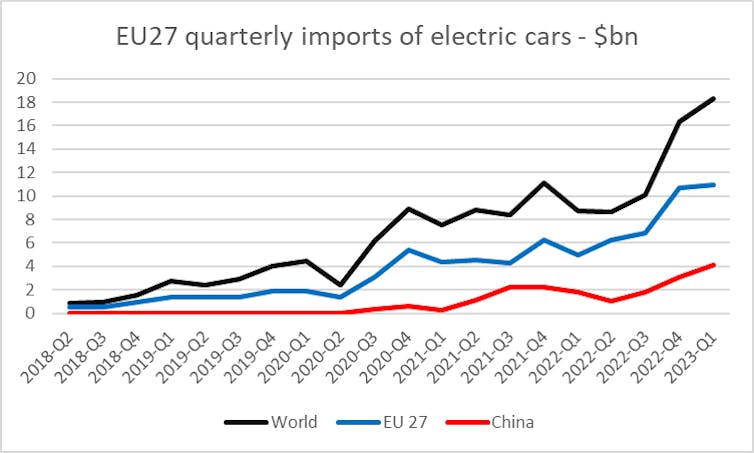

The commission will now undertake the investigation and probably propose new “anti-subsidy” duties on Chinese imports. Although China is the key external supplies of EVs to the European Union, 60% of trade (by value) is within the EU (see graph). Chinese EVs are reported to only make up 8% of EV sales and less than 3% of total EU car sales. However, there are concerns that low prices will enable them to rapidly increase these figures.

The EU is under pressure to react to competition from China’s state-sponsored capitalist model, but it needs to balance the different interests of its member states, as well as wider needs related to the energy transition. The choice to go after EVs is an indication that the commission is taking a harder line with China, but this will not be an easy ride. Europe wants to “de-risk” its bilateral economic relations, by reducing its reliance on Chinese inputs in critical sectors, but it’s far from achieving this objective and mutual dependencies are extensive.

Concerns over Chinese retaliation

A key concern is Chinese retaliation. This long been common in trade defence cases, where targeted countries launch parallel investigations into key imports from the instigating country to pressure them to reduce or remove duties. Germany is particularly exposed to such retaliation, given the importance of the Chinese market for their exports, in particular cars.

Retaliation can also hit completely unrelated products. During the highly political anti-dumping investigation into solar panels a decade ago, China initiated parallel investigations not only into EU exports of polysilicon (an input to solar panels), but also wine, and it threatened an investigation into cars.

The other risks linked to this move have been less widely discussed. China could not only hit EU exports to China, but also by banning or restricting Chinese exports to Europe. The use of export restriction has increased markedly in recent years, both during the Covid-19 pandemic and more widely. China has used the tool extensively to restrict exports of rare earths and other key raw materials. Given the importance of such products for the energy transition, any increase in trade restrictions would certainly have consequences for the EU’s climate objectives.

In addition, the EU is highly dependent on China as a source of EV batteries. Indeed, trade in batteries was almost $20bn last year, while trade in EVs were worth $7.6bn. Although these figures cover several different types of batteries, some were certainly destined for EVs. Should China decide to leverage that dependence, Europe’s EV supply chain would certainly suffer.

Risks of “tariff-jumping” investment

The investigation could also impact on Chinese investment in Europe. Trade defence measures can encourage foreign direct investment (FDI) through “tariff-jumping” FDI – Chinese investors would invest to produce in Europe and so avoid anti-subsidy duties. However the EU has become much more active in screening FDI in recent years, with concerns about security and vulnerabilities sometimes trumping economics. Several Chinese investments were blocked last year. Yet the EU is still encouraging EV investments, where Chinese companies are key to upscaling the EU’s own domestic battery capacity.

The European Court of Auditors recently warned that the EU’s targets for EVs could be jeopardised by a lack of battery production capacity. Although France was a key proponent for the new anti-subsidy investigation, they are also host to a €2bn investment in a gigafactory in Doaui funded by a majority Chinese company – Envision AESC. This is only one of several mega factories being built in the EU by Chinese investors, including in Hungary and Germany.

Increased trade conflict (and increased investment screening) could jeopardise these investments and with them efforts to create an EU value chain for EV. In addition, investment goes both ways. The majority of EVs imported from China last year were EU brands – like BMW and Dacia – who will now be seeking to avoid the new measures imposed on their goods by their home region. Costs are not the only reason these companies are producing in China. It has important advantages, including in the whole value chain required for battery production.

Although the EU recently agreed on new standards that seek to support the domestic battery value chain, including by imposing minimum levels of recycling, upscaling the industry and securing circularity will take time. EU producers are already under pressure as a result of the requirement in the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that only EVs assembled in the US from batteries substantially made in the US (or a partner with whom they have a free trade agreement) qualify for state subsidies. As a result, several planned EU factories have been shelved or downsized.

An inescapable partnership

More widely, as von der Leyen acknowledged in her speech, the EU has no choice but to engage with China to secure progress on many global issues – and climate change is one of them. In a speech in March, where she launched the “de-risking” concept, this was one of the “islands of opportunity” highlighted. Seeking to block the development of an important “green” export will undoubtedly make constructive engagement more difficult.

The new investigation also comes at the same time as the rolling out of the EU’s carbon tariff, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which will hit Chinese exporters hard. In this context accusations of “green protectionism” from Beijing are likely to increase, undermining hopes of building common approaches to global heating.

Finally, the extent to which such trade defence measures actually protect domestic industry is subject to quite some debate. A key problem is trade diversion, where imports may fall from China, but increase from other similarly low-cost sources, reducing the protection provided to EU industry. I found such effects in my previous work on trade defence measures in solar panels, footwear and textiles.

Although China is a key source of EVs globally, other producers exist. Some, like Thailand, are underpinned by Chinese investment. Turkey is a potential supplier to the EU, and while mainly linked to Western automakers, it still has important relationships with Chinese battery producers. Although these suppliers are marginal at the moment, if the EU imposes anti-subsidy duties on Chinese exports, imports from such countries could increase in response. Although competition from China may be reduced, the protective effect of the measures would be reduced by such trade shifts.

In a highly interconnected world, the extent to which these new measures, if implemented, will actually support the development of domestic EV production is uncertain, while the negative side effects are wide ranging. The next hurdle will be to get a majority of member states to back the move. Voting on trade defence proposals has long been highly politicised with certain members supporting duties and others tending to oppose them. The outcome will be closely watched by all those interested not just in EU-China relations, but also in the EU’s wider green transition agenda. There are no easy answers, but the extensive linkages need to be part of the debate.![]()

Louise Curran, Professor of International Business, TBS Education

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.