The Corradino Lines: still surviving but inaccessible

An old idea, built to a new design, but soon outdated

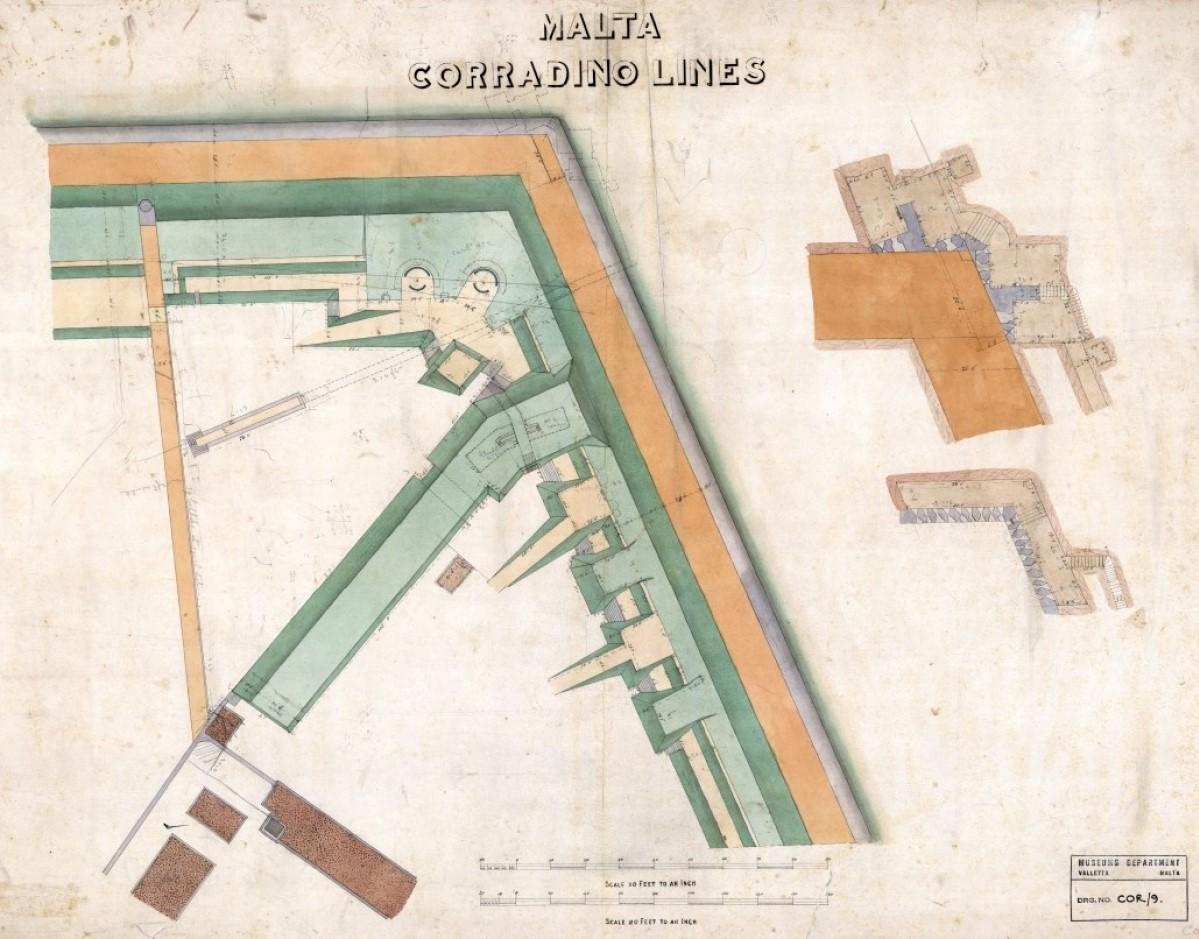

The Corradino Lines were built by the British military, with their construction starting in 1871. Their purpose was to seal off the high ground at Corradino, from where an enemy would have been able to dominate the inner harbour area.

The Corradino Lines consisted of a series of long and straight ramparts set behind a narrow but deep, vertical ditch. The result was a continuous fortified perimeter; from Ras Ħanżir at one extremity, extending to the Cottonera Lines at the other end.

Detail from a map of the Valletta harbours from circa 1895. The Corradino Lines formed a continuous fortified perimeter from Ras Ħanżir at one end and extended to St Paul Bastion in the Cottonera Lines, at the other. Source: UK National Archives

Detail from a map of the Valletta harbours from circa 1895. The Corradino Lines formed a continuous fortified perimeter from Ras Ħanżir at one end and extended to St Paul Bastion in the Cottonera Lines, at the other. Source: UK National ArchivesThe Corradino Lines were the last element of fortification built around the Grand Harbour and, in this respect, they were an extension of the same defensive strategy that had been followed earlier by the Knights of St John. In fact, proposals to fortify the Corradino heights had already been formulated during the time of the Knights. In some schemes, this was conceived as an extension to the Cottonera Lines, then under construction.

Detail from an engraving showing Count Vernada’s proposal, from around 1670, to extend the Cottonera Lines (then under construction) to enclose the Bighi peninsula and across the Corradino heights. Source: Fortresses of the Cross, by Stephen C. Spiteri

Detail from an engraving showing Count Vernada’s proposal, from around 1670, to extend the Cottonera Lines (then under construction) to enclose the Bighi peninsula and across the Corradino heights. Source: Fortresses of the Cross, by Stephen C. SpiteriThe high ground at Corradino faces Senglea and commands the inner part of the Grand Harbour. If enemy batteries were to be established there, they would have been able to bombard Senglea and Cospicua, as well as ships at anchor. This had already happened during the Great Siege of 1565 and during the Maltese blockade of the French (1798-1800).

This long-felt need to fortify the Corradino heights became even more pressing in the 19th century under the British, with the expansion of naval facilities in general and of the dockyard in particular. In 1848, a dock was built in the creek between Cospicua and Senglea, and, in 1862, this was enlarged.

However, with the larger size of warships and the increasing number of Royal Navy ships in the Mediterranean fleet, it became necessary to construct new docks in the creek between Senglea and Corradino. The first of these (Somerset Dock) was inaugurated in 1871. These new naval facilities lay directly below Corradino.

Construction of the Corradino Lines started in 1871. Their layout departed significantly from the design of the earlier Cottonera Lines and the other Grand Harbour fortifications of the Knights.

Screenshot from Google Maps showing the point where the Corradino Lines meet St Paul Bastion, in the Cottonera Lines (right next to the Għajn Dwieli tunnel).

Screenshot from Google Maps showing the point where the Corradino Lines meet St Paul Bastion, in the Cottonera Lines (right next to the Għajn Dwieli tunnel).The Corradino Lines were no longer based on a series of bastions but they were built to the conventions of the so-called ‘polygonal system of fortification’. In particular, the ramparts were laid out as a series of straight lines, which gives this style of fortification its name (a polygon being a geometric form with at least three straight sides and typically five or more).

Although complex and sophisticated in their design, bastioned fortifications were vulnerable to the increasingly accurate fire of rifled guns and the destructive power of explosive shells.

Thus, the profile of the new fortifications became very low, providing a minimal target to enemy fire. And the ditch was made narrower, better adapted to contend with indirect, plunging fire.

As built, the Corradino Lines consisted of a series of long and straight, low ramparts set behind a narrow but deep, vertical ditch, cut directly into the bedrock. This was defended by means of four counterscarp musketry galleries (that is, firing positions built inside the face of the ditch opposite to the ramparts).

The Corradino Lines rampart and ditch. Photo: Ray Cachia Zammit

The Corradino Lines rampart and ditch. Photo: Ray Cachia ZammitThe result was a continuous fortified perimeter; from Ras Ħanżir at one extremity and extending to the Cottonera Lines at the other end.

The most important section of the Corradino Lines was the salient (projecting angle in the fortification) at the top of Corradino Hill. Behind this position, there were emplacements for two 64-pounder guns on disappearing carriages and two ramps intended for the deployment of field guns.

However, while the Corradino Lines were being designed and built, the development of even more powerful armaments continued unabated. And it soon became evident that, if an enemy force succeeded in positioning its guns outside of the Corradino Lines, it would still have been able to target the harbour facilities, even from that distance.

Hence, the need was acknowledged for a new defensive perimeter that would keep any eventual enemy further away from the harbour area, at a distance from where their guns could not threaten the dockyard.

As a result, the decision was taken to fortify the natural escarpment formed by the ‘Great Fault’ in the north of Malta. By 1878, three forts had been built along what later, in 1897, was to be called the Victoria Lines.

The Corradino Lines were retained as an enclosure controlling access within the Corradino heights, a large area being allocated for a parade ground for use by the Royal Navy.

However, when, by 1900, the installed guns had become obsolete, they were simply removed and not replaced. And the Corradino Lines themselves became redundant.

Today, significant parts of the Corradino Lines are still extant. These are in a relatively good condition but they are almost completely inaccessible.

Over the years, Corradino developed into an industrial area and commercial establishments now line both sides of the stretches of the fortifications that survive.

Industrial establishments now line both sides of the stretches of the Corradino Lines that survive. Photo: Ray Cachia Zammit

Industrial establishments now line both sides of the stretches of the Corradino Lines that survive. Photo: Ray Cachia ZammitThe part of the Corradino Lines that used to extend to Ras Ħanżir has been demolished and the rampart now starts from a spot some 200 metres distant, in an area where the ditch has been infilled.

At the Cottonera Lines extremity, the end segment of the Corradino Lines that connects to St Paul Bastion is still extant. The salient section is overgrown with vegetation but it has survived, including the two-tiered, counterscarp gallery at that location. However, the area is not accessible.

The extant parts of the Corradino Lines were scheduled in 2001. Hopefully, this means that those parts that have survived will be saved from being demolished. However, it is still a situation where these fortifications are inaccessible to the public, forgotten and unknown to most. Ideally, this should not remain the case but this is easier said than done. The most impressive part of the Corradino Lines is the salient area. This lies at the back of the Mediterranean Regional Centre for Traditional Chinese Medicine. However, the best vantage point from where to view the salient is from across the ditch, from inside the area currently being used as a depot by Clean Malta – Cleansing and Maintenance Division.

There is a large expanse of land nearby that appears to have been used at one time as a junkyard. It might be feasible to relocate the Clean Malta depot to that site, which would provide them with more space within which to organise their activity. This would make it possible to open to the public the area around the salient, with due consideration for its upkeep and management. This might be undertaken with the involvement of the private sector, as was done very successfully at the nearby ex-military prison.

This is an idea being put forward by means of this article in the hope that it does not end up being just wishful thinking.

Ray Cachia Zammit is the author of the book The Victoria Lines and casual lecturer on fortifications at the University of the Third Age.