Apollo 11 – 55 years later. What if it failed?

US President Nixon had a speech prepared for him just in case Armstrong and his colleagues would not have made it back to Earth

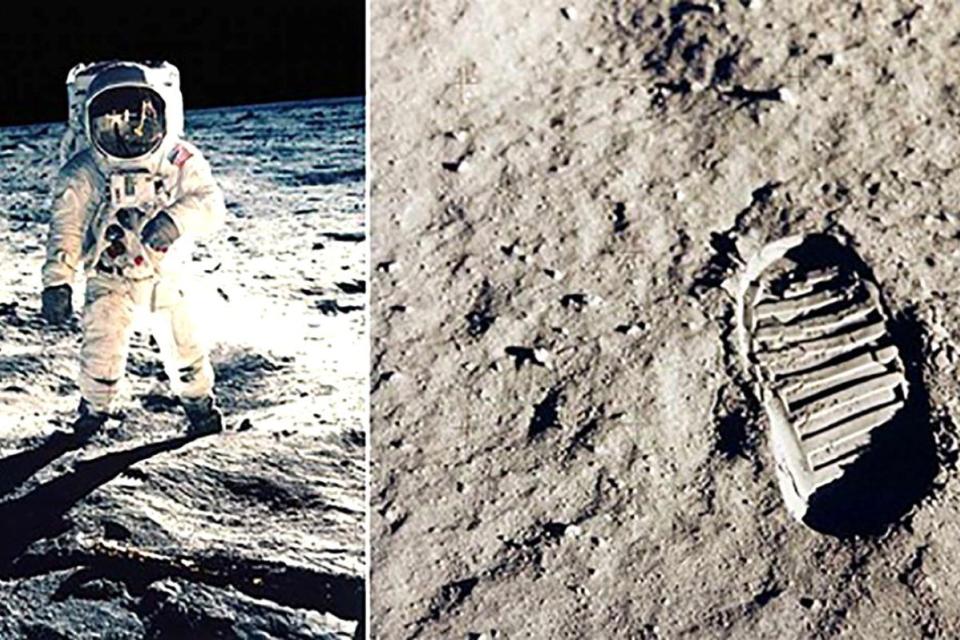

On July 20, 1969 (July 21 in Malta), two astronauts in the lunar module Eagle landed on the moon. This was the first time that man had reached the moon.

“Houston, Tranquility Base here, the Eagle has landed,” the commander, Neil Armstrong informed flight control at Houston.

Armstrong was accompanied by the lunar module pilot Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin, while the third crew member, Michael Collins, orbited the moon on his own in the command module.

Apollo 11 had thundered into the sky above the massive Saturn V booster on July 16, 1969. There was no guarantee that its mission of landing on the moon would be successful. Armstrong estimated a 50 per cent chance of landing on the moon and a 95 per cent chance of returning safely to Earth.

NASA had tested the hardware and software in space. Apollos 7 and 9 had tested out Apollo in Earth orbit and Apollo 8 orbited the moon, while Apollo 10 flew to within a few kilometres of the surface of the moon.

Apollo 11 coasted to the moon and entered orbit on July 21. The lunar module separated from the command module and flew down to the moon’s surface and landed.

It had been a very difficult landing; the computer was overloaded and gave warning alarms. While the computer was guiding the lunar module to land in an area full of rocks and boulders, Armstrong took manual control and hovered before landing in a safe area with just seconds of fuel left.

Mission control: “We copy you down, Eagle.”

Armstrong: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Charles Duke (capsule communicator at Mission Control): “We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

In the event of disaster

The Nixon administration was worried about the risks of the flight, especially that the astronauts would remain on the moon’s surface because their rocket engine would not work.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning Bill Safire was thus tasked by the White House chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, to write a speech that President Richard Nixon would deliver to the American people if Armstrong and Aldrin were marooned on the moon.

It is considered as one of the finest examples of presidential speechwriting:

“Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.

“These brave men, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin, know that there is no hope for their recovery. But they also know that there is hope for mankind in their sacrifice.

The speech Richard Nixon would deliver in case the astronauts were marooned on the moon. Source: https://watergate. info/1969/07/18/an-undelivered-nixon-speech.html

The speech Richard Nixon would deliver in case the astronauts were marooned on the moon. Source: https://watergate. info/1969/07/18/an-undelivered-nixon-speech.html“These two men are laying down their lives in mankind’s most noble goal: the search for truth and understanding.

“They will be mourned by their families and friends; they will be mourned by their nation; they will be mourned by the people of the world; they will be mourned by a Mother Earth that dared send two of her sons into the unknown.

“In their exploration, they stirred the people of the world to feel as one; in their sacrifice, they bind more tightly the brotherhood of man.

“In ancient days, men looked at stars and saw their heroes in the constellations. In modern times, we do much the same, but our heroes are epic men of flesh and blood.

“Others will follow, and surely find their way home. Man’s search will not be denied. But these men were the first, and they will remain the foremost in our hearts.

“For every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.”

The plan was that the president would call each of the widows-to-be when NASA stopped communications with the astronauts. A clergyman would adopt the same procedure as a burial at sea, commending their souls to ‘the deepest of the deep”, concluding with the Lord’s Prayer.

Fortunately, there was no need to use this speech.

They stirred the people of the world to feel as one

Landing and aftermath

As an eight-year-old boy, I watched a grainy television picture as Armstrong put his left foot on the moon when he said: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” It was later revealed that he had intended to say: “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”

The astronauts spent two-and-a-half hours exploring. They collected 21.55kg of moonrocks, took photographs, planted a US flag and set up experiments. One of these, a laser reflector, is still in use today to accurately measure the distance between Earth and the moon.

They had a short conversation with Nixon, who said: “For one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people on this Earth are truly one: one in the pride in what you have done, and one in our prayers that you will return safely to Earth.”

The astronauts returned to the lunar module and safely took off from the surface of the moon and docked with the command module piloted by Collins. They safely returned to Earth. They were kept in quarantine because of the possible risk of bringing dangerous alien organisms from the moon to Earth. But none were found because the surface of the moon is sterile.

The astronauts became celebrities and embarked on a world tour, which was probably more gruelling than their trip to the moon.

The Apollo programme continued with six successful moon landings and a total of 12 astronauts walking on the moon.

There were three major mishaps.

Three Apollo 1 astronauts were burnt to death during a rehearsal on the launchpad. This led to a complete redesign of the spacecraft. Apollo 12 was struck by lightning just after launch but it landed successfully on the moon. An oxygen tank exploded on Apollo 13 but, with the support of ground control, the crew returned safely to Earth but did not manage to land on the moon.

Nobody has returned to the moon since the flight of Apollo 17 in 1972.

Gordon Caruana Dingli is the chair of the Department of Surgery. He is the author of the book We Went to the Moon, published by Kite.