Persons and personalities from Senglea

The reader can detect Fabian Mangion's Rottweiler perseverance in chasing an elusive clue

One of my maternal great-grand aunts from Senglea has remained legendary in family lore. I can’t recall her name, only the nickname by which we affectionately referred to her: iz-zija ta’ ċaċu – a terminal braggart. Lamentably her boast to neighbours ran along the lines of: so many in our family had doctorates that we stretch their parchments on drums (aħna il-lawrji nagħmluhom tnabar).

My parents, who listed boasting firmly among the major capital sins, held her up as the blushingly crass example to shrink away from.

Fabian Mangion, also from Senglea, has every reason to brag about his hometown. It is special in several senses. Even the city’s alternative name, l-Isla, may in itself witness its uniqueness.

The cover of the book.

The cover of the book.Why is Senglea, a promontory and not an island, called l-Isla, l’isola? Simon Mercieca in 2005 offered an ingenious explanation. The peninsula was a personal fiefdom of the grand masters, its inhabitants subject to their special ‘private’ jurisdiction.

In French feudal law, these special enclaves lying outside the general jurisdiction were called Isle, like Île de la Cité in Paris or Isle-de-Noé in Gascony. The French grand masters more connected with that tongue of land, Vedalle and Valette (not de la Valette, Fabian, thank you), would have called ‘their’ peninsula, l’Isle.

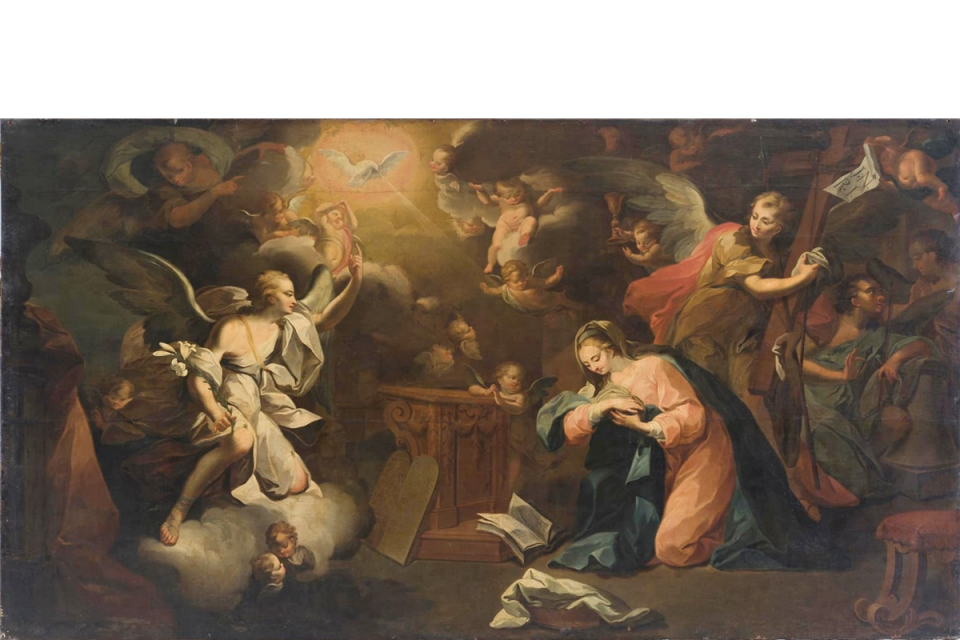

The titular painting showing the Nativity of the Virgin Mary painted by Tommaso Madiona in 1850 for the collegiate church of his hometown.

The titular painting showing the Nativity of the Virgin Mary painted by Tommaso Madiona in 1850 for the collegiate church of his hometown.Senglea has given birth to scores of variably prominent people who helped shape the intellectual, political, cultural and spiritual ethos of the city and of the nation, some of whom still have resonance, others now forgotten, more or less unfairly.

This book covers 33 of them. But there are still many others that Mangion will hopefully see as sequels beckoning. The Senglea Local Council creditably embraced and supported Mangion’s first project. A nudge to keeping up the momentum.

A few numbers. Of the 33 eminent persons, not a single one is a woman, another testimony, if any were needed, as to how insensitive history generally has been to the memory of women.

Those in holy orders number 18. The earliest one, Giovanni Matteo Rispoli, entered his personal vale of tears as early as 1582, but the majority belong to the 19th and 20th century. Their eminence covers the widest spectrum of achievement – artists, musicians, ecclesiastics, bandmasters, theologians, sculptors, authors, teachers.

The pectoral Cross of Bishop Salvatore Gaffiero which, on December 24, 1939, was donated to Senglea’s Onoratti Congregation.

The pectoral Cross of Bishop Salvatore Gaffiero which, on December 24, 1939, was donated to Senglea’s Onoratti Congregation.Mangion has done a wonderful and meticulous job researching and writing up these biographical sketches, relying partly on known material, but also ransacking archives and older publications exhaustively.

The reader can detect his Rottweiler perseverance in chasing an elusive clue, to flesh out the profiles of persons who did not leave very deep imprints on the sands of time. These entries will turn into the necessary points of departure for any future biographical investigation of the personalities captured by Mangion’s radar.

Of the 33 eminent persons, not a single one is a woman

Authors’ choices remain necessarily subjective. Francesco Zahra, a far more challenging painter than the eminently forgettable and sterile Tommaso Madiona, gets six pages in all, while Madiona commands no less 20 and hogs the title of the book. That imbalance appears justifiable, as Zahra has already been amply studied, while Mangion’s work on Madiona is laudably pioneer.

Maybe all the persons whose biography Mangion pursued were impeccably perfect, without a single blemish or weakness. That is the only verdict one can reach reading this book. I’ve never studied these notables myself, so am unable to confirm or gainsay the author.

Carlo Darmanin’s statue of the Scourging at the Pillar for Senglea’s parish.

Carlo Darmanin’s statue of the Scourging at the Pillar for Senglea’s parish.But I still find a gallery of entirely perfect human beings rather two dimensional and unconvincing. Or maybe I was particularly unfortunate in my lifetime, because all the persons I have met and interacted with had good facets and others less good. Biography I do not see as eulogy, nor peans of flattery – it should aspire to critical objectivity, the unravelling of a life in the round. It ought to be the biographer’s aim to accommodate the positive and the negative inherent in all human nature in peaceful coexistence.

Some of these biographies vibrated intimately with me, like the heart-wrenching story of Francesco Tesoriere, a dockyard worker from Senglea, a well-groomed violinist and competent composer.

The chasuble that Mgr Amante Buontempo wore at his first solemn Mass in 1946.

The chasuble that Mgr Amante Buontempo wore at his first solemn Mass in 1946.He ended up arrested and interned together with my father, for the whole duration of the war. Mangion has unearthed the passionate pleas by his doting wife, half-British, addressed to the colonial authorities begging to be told why he had been imprisoned and deprived of his liberty for three years, leaving his family destitute, in dismal poverty. She never received an answer.

Plenty of other Sengleani now deserve to be dissected by Mangion. One who first comes to mind, would be Mgr Ignazio Panzavecchia, leader of a political party that swept to power in the first self-government elections in 1921.

Though hampered by illegitimate birth, Panzavecchia’s middle-of-the road nationalism, his rejection of violence, his compulsion to compromise, his moderation in a time when political hysteria attracted votes, ultimately endeared him to the majority. To everyone’s surprise, he declined the premiership of the first Maltese cabinet, deeming it incompatible with his priestly cassock.

Oil on convas portrait of Bishop Ferdinando Mattei at the Senglea collegiate’s Chapter Hall.

Oil on convas portrait of Bishop Ferdinando Mattei at the Senglea collegiate’s Chapter Hall.I can think of several others too: the lexicographer, author and chess champion Erin Serracino Inglott, Andrea Debono, explorer of the Nile, the entertainers Charles Clews and Charles Thake. Mangion would be the ideal biographer to do full justice to their flair. I would add another controversial Senglean: George Vigo, a gentleman with a pert goatee who ran an elegant man’s fashion shop in Republic Street, Valletta. Vigo was well read, inquisitive and patriotic. Not a troublemaker at all, yet one who did not let go easily.

Vigo fancied himself a historian and put his expertise to the test when income tax was introduced in 1948. He ignored requests to pay, and the commissioner of inland revenue sued him.

He counter-claimed that Malta had not been conquered but had submitted to the British crown by a ‘compact’ which did not confer on Britain the right to determine the constitution of Malta, he pleaded.

The 1947 Constitution was therefore void and so was the Income Tax Act enacted by virtue of that constitution. The court was not impressed. I have seen that lawsuit. It has the taste of great constitutional marmalade.